Before there was a biracial box, the juicy topic of light-skinned Blacks passing for white surfaced again and again in segregated America. In 1912, NAACP leader James Weldon Johnson published the novel The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man , in which a fair-skinned guy witnesses a lynching, and then decides he’s done with the whole Negro thing, and goes undercover as a white man. But when he gets engaged to a woman in his new social circle, he must be honest with her, and find out if her love for him is more than skin deep.

, in which a fair-skinned guy witnesses a lynching, and then decides he’s done with the whole Negro thing, and goes undercover as a white man. But when he gets engaged to a woman in his new social circle, he must be honest with her, and find out if her love for him is more than skin deep.

In the 1920’s, Harlem Renaissance writers often embraced this subject, including Jessie Redmon Fauset in Plum Bun, a novel where the black main character trades on her light skin to gain social sway, but later feels she’s sacrificed, well,  her soul. And then there’s Nella Larsen’s novella, Passing, about two women, once childhood friends, who make different choices: one marrying a white racist and living a lie, the other settling in with her black hubby in Harlem, and becoming active in the community.

her soul. And then there’s Nella Larsen’s novella, Passing, about two women, once childhood friends, who make different choices: one marrying a white racist and living a lie, the other settling in with her black hubby in Harlem, and becoming active in the community.

(The latter story falls along the lines of my grandma, Wilma Johnson, who looked white and married my very brown skinned grandpa. I had thought she passed to shop on New York’s Lower East Side back in the day, but recently Dad said, “She shopped in East Harlem.”)

In Langston Hughes’ poignant short story, “Passing,” a light-skinned black son writes to his mother: “Dear Ma, I felt like a dog, passing you downtown last night and not speaking to you. You were great, though. Didn’t give me a sign that you even knew me, let alone I was your son.”

In a more humorous tale, Hughes’ “Who’s Passing for Who,” two of the people in the story appear to be passing for white, and then black, and then white—leaving the reader’s assumptions thoroughly upended.

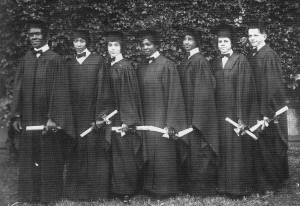

Walter Francis White, far right at his Atlanta University graduation, was both a Harlem Renaissance writer and a passer. But the NAACP leader never stepped out of the race to shed his blackness as if held captive. Instead, he whistled as he skipped along the color line, dipping his toe down on either side to stir things up.

Walter Francis White, far right at his Atlanta University graduation, was both a Harlem Renaissance writer and a passer. But the NAACP leader never stepped out of the race to shed his blackness as if held captive. Instead, he whistled as he skipped along the color line, dipping his toe down on either side to stir things up.

From 1918 to 1930, he secretly investigated lynchings and race riots, reporting on them to raise awareness, and also to champion anti-lynching legislation in Congress. He never managed to get a bill through both houses, but did put mob violence on the map, attracting a host of allies, which served to reduce the number of lynching incidents.

Of Walter’s books, he writes on passing in the novel Flight, where the protagonist initially passes for Caucasian, and then later re-embraces her racial identity. The whole tragic mulatto trope of his time warned the light, bright and damn-near white not to risk crossing over, in part because it could be hazardous to your health if whites found out, but also because it cut you off from family as you nursed a spiritually cancerous secret. Still, at one point in the US, upwards of 13,000 light-skinned blacks a year exited the race, many never to be heard from again.

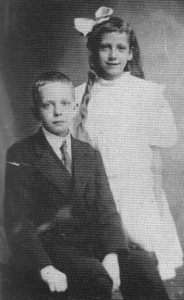

Walter (right: with sister, Ruby) came from a family that could have easily passed. In fact a 1900 census listed them as white. And when his father got hit by a car in 1930, he received great care at the white hospital–until his daughter and brown-skinned son-in-law showed up. That’s when they wheeled the patriarch, still critical from his injuries, straight to the filthy Colored ward, where rats roamed at will. He died shortly thereafter.

Walter’s favorite whipping girl, Oscar-winning Hattie McDaniel—for her series of stereotypical maid roles—got a career jumpstart because of a film that dealt with passing. Imitation of Life (IOL) starred a white woman, Claudette Colbert, and a black one, Louise Beavers, as mothers struggling to raise willful daughters. Till then, black folks were mainly on the margins of Hollywood films, but 1934’s IOL put the two women’s stories on nearly equal footing. The black woman’s greatest challenge was her daughter, Peola, played by uber light-skinned Fredi Washington  (photo at left) who decides to pass for white for more opportunity and less hassle. Peola reclaims her blackness too late, returning home after her mother has died pining for her.

(photo at left) who decides to pass for white for more opportunity and less hassle. Peola reclaims her blackness too late, returning home after her mother has died pining for her.

The upside of this sticky melodrama is that audiences ate it up, demonstrating to a doubting Hollywood that people really would pay to see a black woman co-star—as long as she was dark skinned and plump. Washington never worked in Hollywood again, returning disillusioned to her native New York where she became a journalist for a paper run by (the future Congressman) Rev. Adam Clayton Powell. (IOL got remade in 1959 with Lana Turner and Juanita Moore.)

Over time, passing stories began, well, to fade. In Hughes’ Who’s Passing for Who, his narrator arrives at this: “We literary ones considered ourselves too broad-minded to be bothered with questions of color. We liked people of any race who smoked incessantly, drank liberally, wore complexion and morality as loose garments, and made fun of anyone who didn’t do likewise.”

As we continue to move deeper into an era where gender, race, and sexual orientation are increasingly fluid, people try on identities until they find the one suits them best, as those who would judge wrestle with their discomfort and outmoded expectations.

Photo Credits: B&W Mike, vindicatemj.wordpress.com; Nella Larsen, goodreads.com; Walter at Atlanta University/with sister, White: The Biography of Walter White/Rose Palmer; Fredi Washington, essence.com; Dolezal/Jenner, resourcesforlife.com

PKJ,

Another interesting blog. The subject of passing is a fascinating part of black history, and the writers have used it to demonstrate the complexity of making such a choice. I look forward to reading more of your work.

J

Aww thanks for your support, J.

PASSING wttten by Pamela K. Johnson is a timely article. My cousin in Atlanta called me the other day to tell me that our family members that went passing years ago and the white Foster’s where having a family reunion. They were reaching out to find and embrace the black Foster’s. I was reminded of my father showing me photos of my blonde haired, blue eyed grandfather. My father proudly said his father married the blackest woman he could find. After all the blacker the berry the sweeter the juice… he also said .. but no point in being too Dann sweet. So in reality his mother was btiwn skinned. My father married my mother, light bright and damn near white with Native American Indian blood in her veins. The story of color and passing is always going to be a good story to tell. Well done Ms. Pamela K. Johnson!!! THANK YOU! You have given us all much food for thought!

Wow! That’s good stuff birthday girl! Equally good food for thought. Thanks so much. Hope you have a beautiful day.

Pamela, you and your writings are a treasure and a gift. What a rich essay you’ve give us! I am learning so much from you. Thank you!

Wow! Makes me feel all warm and cherished and everything. Thanks so much for the support, Gay!

Love this! And oh the stories I have in my own family! I never tire of ruminating on the topic.

Absolutely love it, Pam. Keep ’em coming.

P.S. Freddie Washington was my childhood bestie’s great aunt! Many stories there as well.

Love to hear more, Barbara! And thanks for taking time to read and comment!